Bhrikuti Rai, Centre for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

Like most locals from villages dotting the banks of the Indrawati in the Sindhupalchok district of central Nepal, Kamal Ratna Danuwar grew up with stories that revered the river. After all, the perennial waters of the snow-fed Indrawati nourished their fields and gave villagers bountiful harvests twice a year.

Danuwar remembers running barefoot along the banks of the turquoise river with a bamboo fishing rod in one hand and his game in the other. As a young boy, he was told that bringing back anything other than fish was a bad omen. “Not even a pebble,” he remembers his elders berating him. They believed anything brought back from the river would bring home angry spirits since the same river that fed them was also where they performed the last rites of their dead. So, young Danuwar, heeding the elders’ warning, brought home nothing but the fish he caught.

“Twenty-five years ago, we never thought that these pebbles and stones from the river were so precious,” he said. “If only the villagers knew what fortunes these stones hold, they would all have been prosperous by now.”

Danuwar knows very well just how precious the stones from the river are; as the ward chair of Indrawati-12, he has dealt with numerous sand and stone-processing groups vying to set up shops in the areas under his jurisdiction.

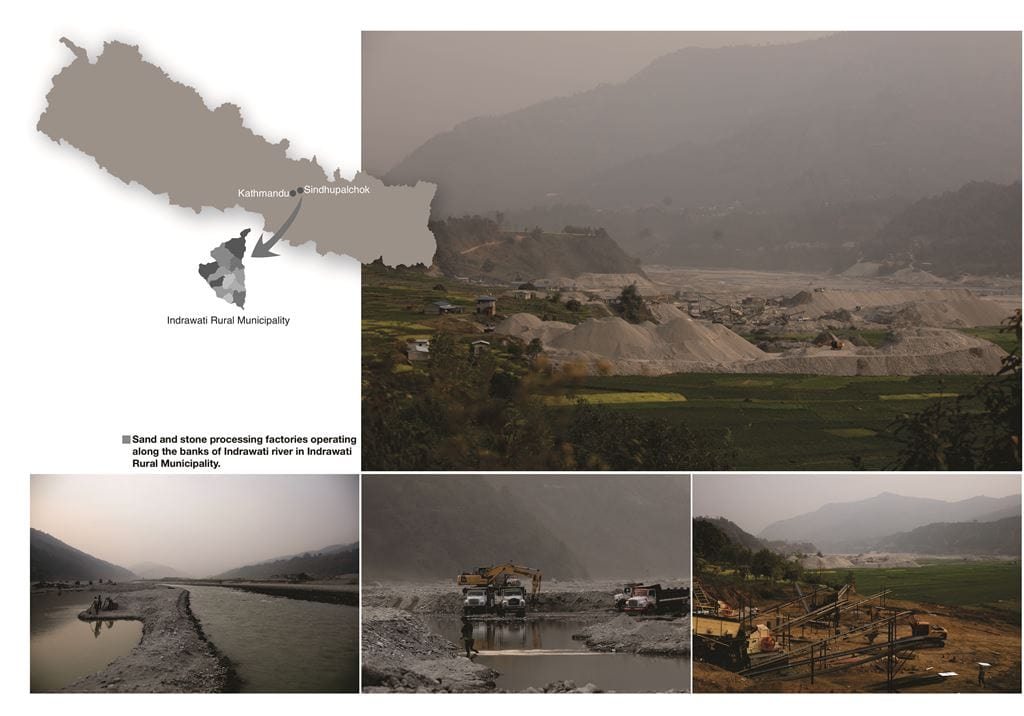

When Danuwar was elected to the office in 2017, there was only one sand and pebble mining firm. Today, Sindhupalchok district’s Indrawati rural municipality alone hosts nine such firms–all of which started operations in the last five years–operating along the river. The banks of the once-pristine Indrawati, which originates on the southern slopes of the Himalaya, are now dotted with rumbling trucks and excavators gouging sand and pebbles from the riverbed, leaving behind tainted waters and pits as deep as 15-20 feet.

The rural municipality calls for tenders to excavate the river, raking in millions of rupees each year. Last year alone, it made about 100 million rupees by selling 7.698 million cubic feet of sand and pebbles, according to officials at the Indrawati rural municipality. This income was nearly 15 per cent of its budget that year, making the river a top revenue earner for the local government.

And, it is not just Indrawati; rivers across the districts that surround the capital city of Kathmandu–Sindhupalchok, Kavre, and Dhading–are being gouged at alarming rates owing to the construction boom fuelled by the pursuit of physical infrastructures like roads, bridges, and the capital city’s urban sprawl. Industries that mine the rivers for sand and pebbles–material vital to construction–are raking in massive profits while sharing the newfound wealth with local governments like the Indrawati rural municipality.

Precisely because so much of their revenue comes from the wholesale plundering of the rivers, the authorities are reluctant to enforce any guidelines that might limit riverbed mining, say locals.

“The ultimate goal is just to collect revenue from the rivers, no matter what the environmental and social costs,” says Anjan Khadka, a tourism entrepreneur from Sindhupalchok.

For the last 10 years, Khadka, along with members from the community, has been demanding accountability from their local leaders and different chief district officers who have come to the district, to protect rivers and livelihoods that depend on them.

They have tried everything, from initiating signature campaigns to submit to the authorities and meeting the leaders in private to organising campaigns, river festivals and marking occasions like World Wetlands Day to raise awareness. Local leaders promise to do better, but they do not always live up to their words, says Khadka, pointing at the banks of the Sunkoshi where excavators and trucks have now become a daily fixture.

“They say they are committed to protecting the rivers, but they call for tenders every year,” says Khadka. “Yes, we need construction materials, but extraction needs to be better regulated.”

Profit over protection

Last April, while the entire country was on the strict lockdown to prevent the spread of Covid-19, with authorities sometimes violently clamping down on people’s mobility, the winding Araniko Highway, which runs past Kavrepalanchok and Sindhupalchok districts, was buzzing with activity. Hundreds of trucks ferrying sand and pebbles were making their way to Kathmandu.

Most crusher plants in Kavre have been found to be violating environmental guidelines, but the lack of strict monitoring and action means these violations go mostly unchecked. Photos: Bikram Rai

Most of the trucks, as media reported then, were carrying riverbed materials from the Indrawati, just months after authorities in Kavre had accused 31 sand mining operators in the district of not following due processes to protect the surrounding environment.

Ranjan Regmi, who was among the officials at the Kavre District Coordination Committee monitoring the ‘crusher’ operators, says this is only what they can do.

“Our job is limited to monitoring and preparing recommendation reports on the crusher factories operating in the district, but we cannot take action,” he says. “It’s up to the local bodies and other agencies to act on our recommendations, which aren’t always implemented.”

Riverbed mining industries fall under the purview of different agencies across all three levels of government in the new federal structure, making the overall monitoring of these extractive industries even more challenging. For instance, crusher factories need a recommendation from local bodies to apply for a license to be provided by the Department of Cottage Industries, which, until two years ago, was a part of the federal government. Before the department gives them a go-ahead, they also need to provide evidence of approval from the mines and forestry departments, which provide them with environmental clearance. Then, once the factory comes into operation, it has to follow guidelines prescribed by local and provincial governments. Finally, monitoring duties fall on a range of authorities, from locally elected officials to the chief district officer and other district-level officials.

But, it is not just the responsibility that is shared among the different levels of government; so are the profits.

Even as the revenue sources dried up due to the pandemic, money from sand and stone extraction continued to fill state coffers. Data from Bagmati province–the most populous province with the highest budget allocation–shows that revenue generated from sand and boulder mining at the local level continued to be the single largest contributor to the province’s coffers, even during the four-month nationwide lockdown.

According to an official from the Jagati checkpoint in Bhaktapur, over 600 tipper trucks carrying sand and pebbles from the nearby districts of Kavre and Sindhupalchok enter Kathmandu each day.

The Intergovernmental Fiscal Management Act stipulates that local bodies are required to contribute 40 per cent of their revenue generated to the provinces. This incentivises the provinces to turn a blind eye to overexploitation or environmental degradation at the local level as they make most of their revenue from these very industries.

Officials at the Bagmati province’s Ministry of Economic Affairs and Planning have projected earnings from sand and stone mining at the local level to cross Rs two billion this fiscal year. However, until early 2021, only about Rs 250 million, just 12.21 per cent of the projection, has trickled in.

Hundreds of trucks make their way from the riverbanks of Kavre, Sindhupalchok and Sindhuli to Kathmandu every day, carrying sands and pebbles. This photo is taken at Sanga, the valley’s eastern entry point.

Last fiscal year (2019/20), Bagmati province received over a billion rupees in revenue from local bodies, of which 93 per cent, about 98 million rupees, came from sand and stone mining. This was almost double the Rs 52 million that the province had received from riverbed materials in the previous fiscal year (2018/19). Kavre, Sindhupalchok, Dhading, and Lalitpur are among the highest contributors to Bagmati province’s coffers. Officials in the province also say the huge difference between the years might also have resulted from many local bodies not reporting their earnings to the province on time.

But, even experts at government bodies warn that relying on riverbed materials for quick and easy revenue is leading to the over-exploitation of natural resources. Juddha Gurung, an environmental expert who is also a member of the Natural Resources and Financial Commission, a constitutional body, says that “short-term gains” are leading to exploitation.

“If elected leaders decide to continue exploiting as much as they can during their terms, these resources won’t last long,” says Gurung. “They should be mindful that such aggressive extraction is going to leave the rivers scarred, and there will be nothing left for future generations.”

Conflict of interest of elected officials

Environmental activists say that things have gotten worse after the local elections of 2017 when a number of candidates with ties to the mining and construction industries received election tickets. In Kavre and Sindhupalchok, people like Ganesh Lama, Tirtha Lama, and Chandra Lama–all with investments in various crusher plants, according to documents from the federal Department of Cottage and Small Industries–contested the elections. While only Chandra Lama won in 2017, Tirtha Lama was a member of the second Constituent Assembly. According to a 2018 report by the Center for Investigative Journalism, a quarter of all elected representatives at the local level have ties to the construction business.

As a result, authorities do not always prioritise regulation of the lucrative mining business. Advocate Chiranjivi Bhattarai, who filed a lawsuit at the Supreme Court in 2019 seeking to stop illegal sand mining in the Sunkoshi river, says he does not have much hope. He is still awaiting a decision in the three-year-old case.

“The overarching influence of interest groups from the mining industry doesn’t allow authorities to act effectively to stem the rot spreading across Nepal’s rivers and hills,” says Bhattarai.

Long-term harm

Uncontrolled extraction of the rivers is a double-edged sword. While there might be profits in the short term, overexploitation will eventually end up damaging the fragile environment of Nepal’s mid-hills.

River ecologist Ram Devi Tachamo Shah of Kathmandu University says uncontrolled river mining, where excavators dig several metres deep, has altered the ecosystem beneath.

Chandra Bahadur Majhi

“These activities don’t allow the natural habitats in the river ecosystem to thrive,” she says, “and when minerals and algae from riverbeds are extracted while scooping out large amounts of sand and pebbles, there will be a massive decline in ecological diversity.”

These short-term gains also threaten to hurt the local economy of districts like Sindhupalchok, which is trying to tap its rivers to promote watersports and attract tourists. This is already worrying Sindhupalchok-based tourism entrepreneur Anjan Khadka.

Khadka says his interactions with local authorities in Sindhupalchok leave him frustrated and angry. What makes it worse, he says, is that having leaders from the district and neighbouring Kavre in high-profile state positions–like House Speaker Agni Sapkota, former ministers Sher Bahadur Tamang, Gokul Baskota, and Arun Nepal–has not made a difference when it comes to regulating these exploitative industries.

“They talk about environmental protection with such enthusiasm in public forums,” says Khadka. “But, when it comes to making decisions, they don’t do anything to prevent exploitation.”

Recalling the fanfare with which local and several high-profile national leaders, including Speaker Sapkota, announced a 10-point declaration during Sukute Festival in early 2020 to conserve rivers and better regulate riverbed mining, Khadka says, “Their commitment to developing the district’s rivers as a hub of tourism are just empty words.”

Locals who live near the processing plants on the banks of rivers like Indrawati, Sunkoshi, and Roshi also say their communities are suffering because of inaction.

Chandra Bahadur Majhi comes from a family of fishermen in Majhitar, a small village in Sindhupalchok. He is well into his seventies and has spent all his life farming, fishing, and ferrying people on rickety boats across the mighty Indrawati, like most people in the fishing community of Majhis traditionally did. But, today, the river does not look the same. He gets nostalgic and worries about the Indrawati river.

“There are hardly any fish left in the river anymore,” he says looking at the fishing net rolled up in a corner of his room. “All that roaring and thundering from the machines gnawing at the rivers probably scare the fish away.”

Passing the buck

But, crusher plant operators say it is unfair that only they receive criticism. Kuber Singh Shrestha’s Jaldevi Stone Pvt Ltd was one of the first plants to operate in Indrawati back in early 2017 when village development committees were still the governing local bodies. When he applied for permits then, he was told that crusher plants needed to be one kilometre apart from one another. But, in the absence of a strict monitoring mechanism in place, there are now many such plants operating every few hundred metres on the banks of the Indrawati. That, he says, is not the industry operators’ fault alone.

Uncontrolled riverbed mining not only disfigures the river, it leaves behind tainted waters and pits as deep as 15- 20 feet.

“If the authorities were so worried about the river and the environment, they could easily limit the number of permits for these plants,” he says. “Yes, rivers are being exploited, but the government has given them permission to do so.”

Gobinda Sapkota of the Community Development and Environment Conservation Forum in Sindhupalchok says he is not surprised by the state’s unwillingness to better regulate these industries. Over the last decade, he has seen local communities struggle with growing water shortages, river pollution, and a disruption of their traditional ways of life because of uncontrolled riverbed mining.

“The rivers are only there for businesses and local bodies alike to plunder and make money,” he says. “Meanwhile, people are bearing the brunt of the consequences, breathing in the dust from these industries all day and watching rivers get polluted.”

But, local officials like Bansha Lal Tamang, the chair of Indrawati rural municipality, say they have no option but to call for tenders worth millions of rupees each year, sometimes often at the cost of the environment.

While he calls his administration “environment-conscious”, he also says that they rely on the revenue from riverbed extraction for the local government’s operations and programmes.

“The central government hasn’t yet been able to help us manage human resources, so we use the revenue generated from these industries to hire technicians in agriculture, veterinary science, engineering etc, as well as for programmes to build river embankments.”

Since Tamang’s election, four new plants have been given permission to operate with one more in the process of starting operations.

Living with the consequences

The 2015 constitution clearly states that the three levels of government have the authority to make their own policies regarding natural resource use and collect revenue generated from the same. While there are issues with fiscal policy and revenue sharing in the federal structure, experts say local levels should take steps to build up their revenue pool, which is informed by a sound policy.

“Right now, local governments are taking the easy route by haphazardly selling riverbed materials,” says local governance analyst Khim Lal Devkota. “If they want to come up with sustainable solutions, they can easily formulate joint policies with other local bodies and regulate these industries.”

But, with no clear demarcation of responsibility when it comes to regulation, local bodies are quick to pass the buck to someone else. Meanwhile, it is the locals who have to live with the consequences.

Along the winding BP Highway, where rivers from the hills flow towards the southern plains, excavators clawing the riverbanks and hills leaving a blanket of dust have become a common sight, particularly in Roshi rural municipality. Named after the Roshi river, the municipality rakes in millions of rupees by selling the river’s resources. Last year alone, it made Rs 50 million.

But, all six crusher plants registered at the municipality have been flagged by the Kavre District Development Committee for not meeting guidelines to protect the environment–from being situated too close to forests and human settlements to polluting the environment with no mitigation measures.

One such industry is the Om Satya Sai Crusher, whose operations lie just a few hundred metres from the highway and the municipality office. But, Roshi rural municipality officials, who can hear the whirring of Om Satya Sai’s machines from their office, say they cannot do much.

“Yes, it has made the surroundings dusty and it brings in material from outside to process here, but we aren’t the ones who gave them the licence to operate; it was the Department of Cottage Industry, which falls under the federal government,” says Dambaru Dahal, the seniormost bureaucrat there.

Upendra Nath Gautam, a Roshi local, regrets leasing 10 ropanis of land to the factory.

“They said they would ensure that locals got a job and that the fields nearby wouldn’t be disturbed, but look at what they’ve done,” says 65-year-old Gautam, gesturing towards a blanket of dust rising from the factory site, a few hundred meters from his poultry farm. “I feel guilty sometimes, seeing my neighbours’ homes and fields covered in dust.”

Bhrikuti Rai is a Bertha Fellow.